Photos credit: SVPhilon/iStock / Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

Respirator Use in the Restoration Industry

Awareness and Effort:

Part 1 of 2

By Barry Rice, CSP

Restoration industry work has the potential for serious breathing hazards. They may be evident before even walking into the building – in the form of odor or dust – and provide advanced warning. However, some are not detectable (e.g. asbestos) and provide no warning. Then there are the hazards created by our own work (e.g. cutting and tearing out materials) and the chemicals we bring into the building to perform our services.

Photos credit: Ekspansio/E+ via Getty Images

Most restoration professionals are aware of these hazards and the need to protect themselves. As an industry, we have excellent education and certification resources (ANSI, IICRC, RIA, NIOSH, etc.) that teach us about the hazards and how to protect ourselves. However, respirators are not always used properly and sometimes not worn at all. For example, cartridges may not be changed, masks not cleaned and sometimes the health risk is trivialized. Then there are the neglected or misunderstood regulatory requirements. These are easy pitfalls to slip into. However, through awareness comes the understanding of the need for additional effort.

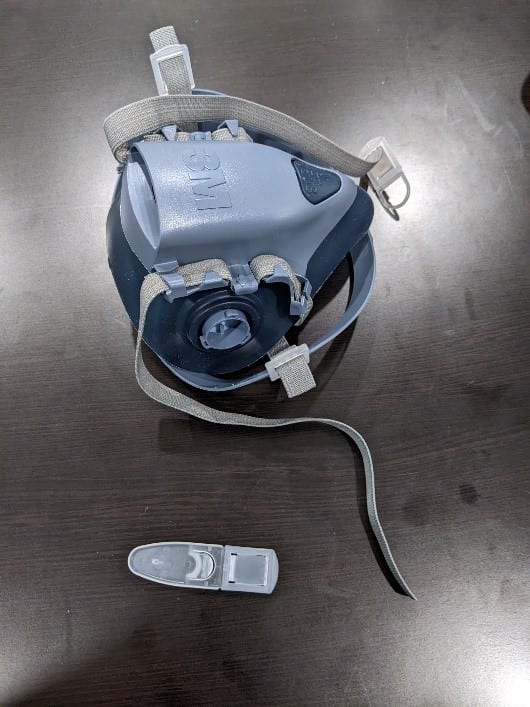

Photos credit: Barry Rice)

I hope to create that awareness and identify the effort necessary to protect restorers from respiratory hazards in my next two articles. This first article will cover the steps to correctly set up a respiratory protection program. The second article, next month, will cover how to implement and follow your program. I will not sugar coat the effort; there are few shortcuts and there is a time investment. However, the effort is well worth it to protect our lungs!

Program Creation

I will start with what may be the biggest challenge: Taking time to create the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) required written respiratory protection program.1 Fortunately, the contents of the written program are pretty clearly identified in the OSHA standard. Some key contents include:

- Your respiratory hazards, typically broken down by job type

- When to wear respirators

- What respirators and cartridges to wear

- Medical evaluations

- Fit tests

- Training

- Maintenance and care

- Voluntary use of respirators

- Review of your program’s effectiveness

Resources for a Written Program

Here is where the proverbial pen meets paper (fingertips meet keyboard?). Restorers can pull up OSHA’s respirator program requirements1 and begin writing their own program. This was basically the only way to create a written program prior to the convenience of internet downloads. Much like the three-ring binder safety data sheet (SDS) collection method I mentioned my February 2022 SDS article, there is nothing wrong with this method. However, if you have little experience with respirators, regulations and writing procedures, this manual process may overwhelm you.

If you do not have the experience or inclination to write your own program, there are many resources for what I call “fill-in-the-blank” program documents. I am familiar with the following resources; you may be able to find others.

- OSHA’s Small Entity Compliance Guide for the Respiratory Protection Standard, OSHA 3384 09 20112

- State OSHA programs (e.g. Michigan’s LARA/MIOSHA Sample Respiratory Protection Program)

- Your restoration franchise organization

- Your worker’s comp insurance provider

- Business or industry organizations you belong to

- Online resources

- Customized programs from a safety consultant

If you ever doubt or are unsure about a program’s compliance with OSHA, take the time to compare it to 1910.134(c) requirements or have a safety professional do that for you.

Areas of Focus for Restorers

Having spent years managing respiratory protection programs for restoration companies, I can recommend you spend a little extra time on the topics mentioned in this paragraph when creating your written program. You will save the time, money and effort of any future rewriting by immediately customizing your program for the work you perform.

From a general organizational perspective, be sure to assign a coordinator for your company and let them become the go-to person for anything related to respirators. Have them help with writing the program, purchasing and stocking respirators/cartridges, coordination of medical evaluations / fit testing, etc.

Perform a breathing hazard evaluation for your work. This is as simple as creating a list of work tasks and contaminants in the air that require employees to wear a respirator. Put this list in writing and include it in your program. I have found that a basic spreadsheet works just fine for this. Trust me; you will refer back to it in the future.

Here are some work tasks with respiratory hazards that are common in the restoration industry:

- Mold inspections and remediation

- Chemical/cleaner/disinfectant use

- Misting and spray applications

- Sewage/Category 3 water cleanup

- Biohazard/trauma/crime scene cleanup

- Fire damage inspection and restoration

- Dusts (wood, silica)

- Fibers and other particulates (asbestos, fiberglass)

Clearly identify the proper respirator and cartridges for the work tasks in the breathing hazard evaluation. Much like the blank written program, there are many resources for this. Here are a few off the top of my head:

- Safety data sheets

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) guides (e.g. mold)

- Industry standards, training and certifications (IICRC, RIA)

- Industry association documentation and publications

- Written recommendations from industrial hygienists (e.g. mold protocols)

- Manufacturer’s online respirator selection guides (3M, Honeywell/North, etc.)

Finally, identify the OSHA-required cartridge change-out schedules for your work tasks.3 There is no specific indicator of the end of life for a cartridge. Generally speaking, resistance to breathing will increase (from particulates), or the wearer will begin to sense smell or taste from a vapor or odor. So, the change-out frequency can be challenging if this is your first respirator program or you do not have experience with cartridge use. I recommend using information from the below links and starting out with short change-out frequencies.

- “Cartridge Change Schedules for Low Exposure Environments” (https://multimedia.3m.com/mws/media/1282560O/tbd-241.pdf), from 3M

- “Cartridge Change Frequently Asked Questions” (https://multimedia.3m.com/mws/media/259820O/3m-cartridge-change.pdf), from 3M

Powered Air Purifying Respirators (PAPRs)

Every year, I speak with more restorers who have started using PAPRs to replace conventional half-face or full-face respirators. I can best describe a PAPR as a respirator that uses a blower to pull air through cartridges and then push the filtered air down across the wearer’s face and out the bottom of a hood or mask. PAPRs provide a number of advantages over traditional tight-fitting respirators:

- Can be worn with a beard

- Are loose-fitting and do not require a fit test (do require a medical evaluation)

- Have lower breathing resistance

- Provide some heat relief due to the air flow

- Provide greater protection to the wearer

Of course, most alternatives have trade-offs. PAPRs are much more expensive than a traditional half-face or full-face respirator. However, the restorers I talk to who use these are huge advocates of investing the money into PAPRs. I could write an entire article on PAPRs (maybe in the future). If you think they may be beneficial to your work, contact a respirator manufacturer to learn more.

Gray Areas for Restorers

I would be remiss if I did not point out OSHA requirements that, to the best of my knowledge, are an unknown for restorers. Specifically, the selection of Assigned Protection Factors4 and Maximum Use Concentrations for respirator use around gases and vapors.5 Selecting these factors and concentrations is beyond the technical limitations of this article. Further, I have not seen measurements of gas or vapor concentrations during the application of cleaning chemicals, deodorizers or disinfectants for the restoration industry. These measurements, along with other data, would be necessary to select the factors and concentrations. I strongly recommend using the resources I have identified (SDSs, EPA guides, industry standards, manufacturer guides, industrial hygienists) to make your selections and then save that information for future reference. If any readers have specific restoration industry data for these criteria, I welcome further information and insight!

Summary

As you can see now, there is significant effort required to write a respiratory protection program. However, I feel it is a critical component of a restoration business based on the type of hazardous environments we work in. Further, once complete you can rest assured that you are protecting your technicians’ health and shielding your business from potential liability. My next article will help you implement and follow your written program. Until then, please let me know if you have questions or issues writing your program!

Reference:

- 29 CFR 1910.134(a)

- https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/3384small-entity-for-respiratory-protection-standard-rev.pdf

- 1910.134(d)(3)(iii)(B)(2)

- 1910.134(d)(3)(i)(A)

- 1910.134(d)(3)(i)(B)

Barry Rice is a Certified Safety Professional (CSP) with over 20 years of experience. He is the Environmental, Health and Safety (EHS) director for Signal Restoration Services’ family of companies that includes Signal, US Roofing and PuroClean. Rice has supported EHS efforts in various industries, including environmental restoration, heavy industrial manufacturing, mechanical field service, automotive and aircraft manufacturing support, residential and commercial construction, and disaster restoration. If you have questions or would like to speak to Rice, he can be reached at (248) 878-5662 or barrynrice@gmail.com.