When It Works,

It Works

Photo edited from Heiko Küverling/iStock / Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

Determining a Proper Criteria for Evaluating When a Mold Remediation Project Is Finished...

By Michael A. Pinto and Jacob Kooistra

According to the Merriam Webster Dictionary, the definition of “If it ain't broke, don't fix it” is an informal way to say that one should not try to change something that is working well. It is attributed to Bert Lance, the director of the Office of Management Budget during the Carter presidency. Like most idioms, this one gets overused and misused. However, when talking about criteria for judging the successful completion of a mold remediation project, it actually applies quite well.

The Advent of the Mold Remediation Industry Was a “Surprise”

Many professionals now working in the mold remediation industry were not present at its inception. For them, mold remediation has always been a subset of restoration along with fire, water and contents. The fact is, just over two decades ago mold remediation burst into the consciousness of restoration professionals because of a massive lawsuit in Texas. In that case, the policyholder sued their insurance company because the dry down of a water loss went horribly wrong. It was claimed that the response to the water intrusion led to mold growth to such an extent that the occupants of the home all became ill. Eventually, after years of wrangling, the multi-million-dollar structure was demolished. 1

In a very short time, everybody was aware of the potential problems with mold. Guidelines were developed, standards were written, training classes were developed, certifications were designed and a number of states started regulating the work. However, as the mold remediation aspect of restoration grew into its own subset of the industry, one thing was missing: A universally agreed-upon criteria for determining the difference between a successfully completed mold remediation project and one where additional cleaning was necessary. Part of this was due to the fact that early in the development of the industry there was debate over which sampling technique was most appropriate.

The development of the mold remediation industry ran parallel to the introduction and acceptance of spore trap samples, as compared to the traditional culture sampling using petri dishes. Within just a few years of their introduction, spore traps became the sampling method of choice for most mold remediation professionals. Still, the ability to collect a spore trap sample and then analyze it brings the need for comparison criteria for the data.

Figuring Out What Spore Trap Sample Results Really Mean

Over the past two decades many additional sampling techniques for fungal material have been announced beyond culture samples and spore trap samples. The introduction of sampling systems with names like ERMI, HERTSMI, EMMA and INSTASCOPE present the mold remediation professional with a plethora of options, each claiming to be the best, and often the newest, technology to once and for all solve all of their sampling needs. Few mold professionals have the time to really dig into what any one system actually can and cannot do for them. We will leave the discussion of multiple sampling systems – and their appropriateness for initial investigations, pre-work sampling and post remediation – for a future article.

The purpose of this discussion is to revisit the notion of a spore trap “Clearance Criteria,” and discuss what such a standard is and why it can be useful to everyone involved in a mold remediation project. Because of the turnover of professionals in the industry over the last 20 years, we will focus on a long-established spore trap post-work verification criterion as a teaching example.

The Parameters of a Good Clearance Criterion

A post-remediation clearance criterion has to meet certain basic requirements before it can be useful to anyone. As a starting point, in order to be standardized and become robust, a clearance criterion has to be universal. This means that it should be appropriate for multiple projects in varied situations.

To be truly useful across projects, a post-remediation clearance criteria needs to be unambiguous. A useful standard will eschew terms like the IICRC S520 “normal fungal ecology” or the insurance policy “pre-loss condition” in favor of fixed numerical end points. The use of a flat value, such as less than 2,000 spores per cubic meter of air, allows a standard to be useful in multiple environments and from project to project, often without the need to conduct pre-work sampling. Additionally, by setting a numerical value on “clean” that is not tied to the relative local conditions, meeting or exceeding the industry standard of care can be a natural part of each project.

Why a Post-Remediation Clearance Criteria Is So Important

After discussing what a post-remediation clearance criterion needs to be, the natural question is, “Why should my business use such a standard?” There are three primary reasons why any consultant or contractor might choose to utilize a standardized clearance criterion.

- First, by always shooting for the same target as the end point of every remediation project, it can help create crew efficiency as everyone involved in the project can be aware of where the goal posts are and be encouraged to take the steps that get them there. The metaphor may be old and a bit tired but it is still true that a boat only gets to where it needs to be when all the rowers pull at the same speed and in the same direction.

- Second, by voluntarily submitting to a work completion end goal that is more stringent than the vague industry standards, a contractor can both use that excellence as a piece of marketing information and, if consistently followed and met, as a partial defense against liability if a project turns sour post work completion.

- Finally, and perhaps most useful to the contractor and homeowner alike, by utilizing a fixed standard regarding what project completion and clean will look like, the contractor and the client can start and end the remediation project on the same page. By laying the groundwork for a mutually satisfactory end point from the very beginning of the contract, the client can be certain what level of service they are buying and the contractor can know what they have to do to meet their obligations. Using an airline analogy, having a post-remediation clearance criterion is the same as agreeing where the flight is landing before booking the tickets.

Is There Such a Post-Remediation Clearance Criterion?

Understanding the importance of having a universal and realistic post-remediation clearance criterion, the team at Wonder Makers Environmental developed a white paper in 2004. This paper was based on a review of previous research studies from around the world where air quality experts had looked at mold levels and classified them from a health or acceptability standpoint. From these studies the details of what constitutes “normal” versus “clean” environments was statistically determined. The methodology of the work was validated by the fact that it was published in the peer-reviewed journal, Professional Safety, in November 2004.

The publication of this practical example of a functional standard was well accepted from the start. Because of the journal publication, the clearance criteria was not kept proprietary and was free to industry, with only the standard attribution due for any published material. As such, the criteria developed by Wonder Makers Environmental has been in use for over 15 years. During that time, additional validation studies have been produced and shared at various industry association events. More importantly, its use has expanded globally, and been incorporated into recommended project guidelines by many organizations and industry associations such as the National Organization of Remediators and Mold Inspectors (NORMI).

So, What Is It?

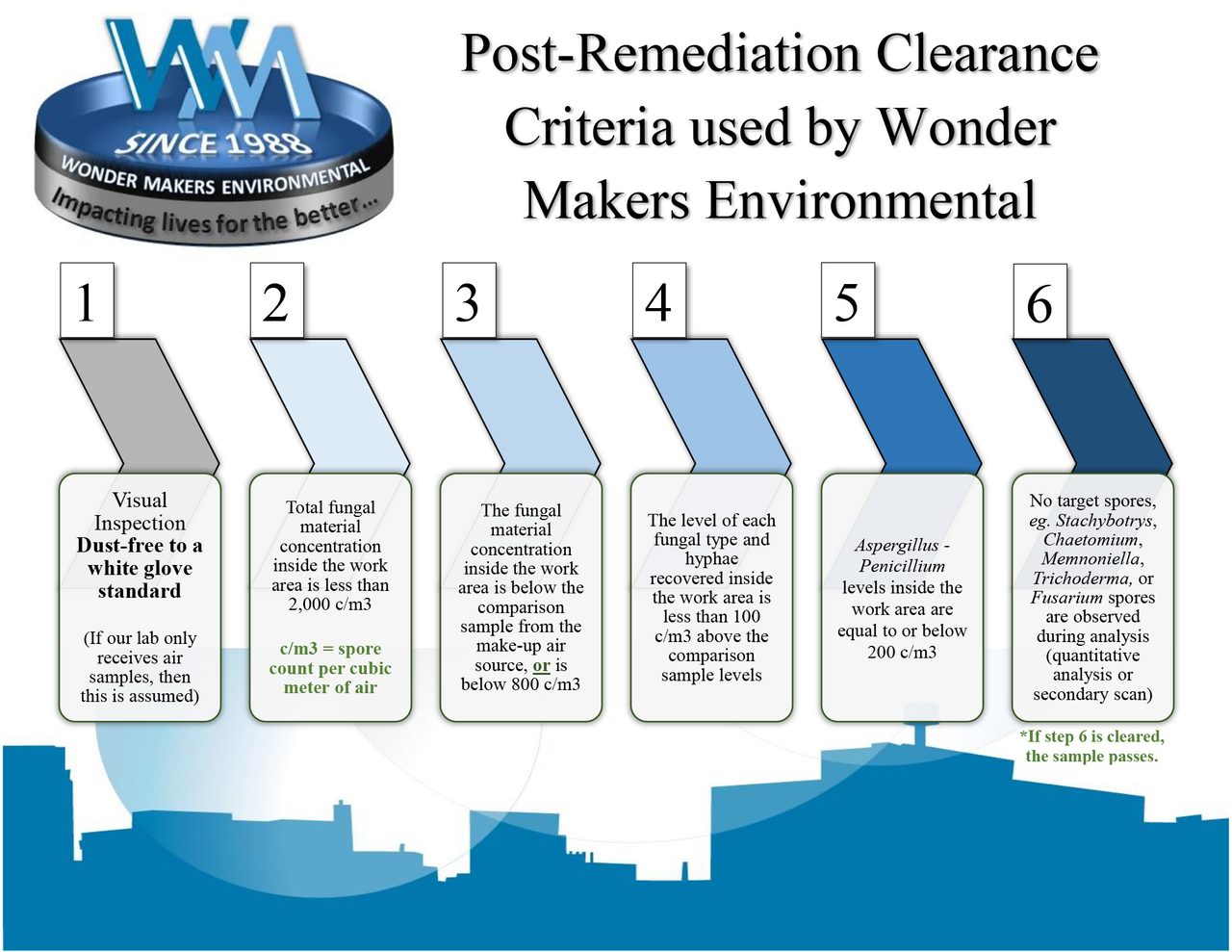

Wonder Makers developed a “Clearance Standard” that is a straightforward criterion, but it only applies to spore trap cassettes. It is an example of an easily understood definition of clean that exceeds the industry standard of care. In six steps, the Wonder Makers Clearance Standard works like this:

- Visual inspection dust free to a white glove standard

- Total fungal material concentration inside the work area is less than 2,000 spore count per cubic meter of air (c/m3)

- The fungal material concentration inside the work area is below the comparison sample from the make-up air source, (or) is below 800 c/m3

- The level of each fungal type and hyphae recovered inside the work area is less than 100 c/m3 above the comparison (out of doors) sample levels

- Aspergillus - Penicillium levels inside the work area are equal to or below 200 c/m3

- No target spores, e.g. Stachybotrys, Chaetomium, Memnoniella, Trichoderma or Fusarium spores, are observed during analysis (quantitative analysis or secondary scan)

What Makes This Better Than Other Approaches?

How does what was discussed earlier about a solid standard apply to this criterion? On a basic level, it is a good working definition of clean for the air quality relating to fungal material in the air that can be applied to almost any structure. If a work area can meet this standard, it is almost certain that the work completed there was effective enough to be within the industry standard of care. Additionally, almost any technician, homeowner, office manager or project manager can take a sample result report from nearly any laboratory and, by following the steps, determine if the sample is clean enough to justify pulling down the containment barrier.

Probably the most important aspect of the post-remediation clearance criteria that needs to be shared with a new generation of mold remediation professionals is the fact that it works, and has done so for a long time. The projects that fail need more work before the environment is ready for occupants. The ones that pass do not result in additional problems after the fact. Indeed, this criterion is a good current example of following the idiom, “If it ain't broke, don't fix it.”

Looking Toward the Future

While similar standards have yet to be developed for many of the new sampling techniques now coming to market, that does not preclude the fact that in the future, the technologies that persist with the industry will need a clear sample interpretation guide to help them transition from being a niche product only utilized by environmental professionals to a normal part of the post-remediation sampling process. As these new sampling systems begin to see more use, and the data accumulates relating to what a clean environment looks like, a similar standard will begin to emerge that establishes the same premise on different grounds, since ultimately clean will never be mold free, but it will always be clean.

1Any Google search of the term “Melinda Ballard Mold Case” will bring up tens of thousands of references in a split second.

Michael A. Pinto is chief executive officer of Wonder Makers Environmental, Inc. He has earned six professional designations including Certified Safety Professional (CSP) and Certified Mold Professional (CMP). Pinto is the author of over 230 published articles and several books including, Fungal Contamination: A Comprehensive Guide for Remediation. He has volunteered extensive time and expertise for the development of the RIA Forensic Restoration Guidelines, IICRC S520 standard for mold remediation, and the RIA/IICRC/AIHA white papers explaining proper procedures for addressing the SARS CoV-2 through cleaning and application of disinfectants. He can be reached at (269) 382-4154 or map@wondermakers.com.

Jacob Kooistra is an environmental specialist with Wonder Makers Environmental, Inc., a manufacturing and environmental consulting firm that specializes in identification and control of all types of indoor contaminants. For 10 years, Kooistra has worked in the property restoration industry, specializing in mold remediation and caring for sensitized individuals. In his current position, Kooistra assists building owners and occupants when they face indoor air challenges related to mold, lead, asbestos and chemicals. He can be reached at (269) 382-4154 or jsk@wondermakers.com.